One in five people experiencing homelessness in Los Angeles County are women facing homelessness as individuals, meaning without a partner or children, and most of them are women of color.

These numbers are growing. Between 2015 and 2022, the overall number of women experiencing homelessness in Los Angeles County spiked from 13,544 to 20,724, a 53 percent increase. Among them, the number of women experiencing homelessness as individuals also increased, reaching 14,403 in 2022, or 69 percent of all women experiencing homelessness in the county. Moreover, 75 percent of women experiencing homelessness as individuals reported residing in unsheltered locations, such as the street or in cars.

The number of women of color experiencing homelessness as individuals has also increased significantly in just a few years. Between 2020 and 2022, the number of such women in Los Angeles County increased by 14.4 percent, while overall homelessness in the county increased by just 2.2 percent.

These trends are alarming. Research shows that women experiencing homelessness may face more negative outcomes from homelessness than men, such as a greater likelihood of being violently attacked. Unsheltered homelessness, in particular, has negative impacts on women’s mental and physical health, including a greater likelihood of poor mental health, alcohol use, and noninjection drug use.

Recognizing these patterns and the need for urgent change, the County of Los Angeles named “unaccompanied women” a unique group of people experiencing homelessness and tasked the Los Angeles County Homelessness Initiative with carrying out the first-ever countywide women’s needs assessment. (While the term “unaccompanied women” is the official subpopulation term designated by Los Angeles County, we use the term “women experiencing homelessness as individuals” to better reflect women’s lived experiences.) In partnership with the Downtown Women’s Center, the Homelessness Initiative recruited the Urban Institute and the Hub for Urban Initiatives to conduct the Los Angeles County Women’s Needs Assessment, the largest and most rigorous study to date on women enduring homelessness as individuals. Nearly 100 women participated in listening sessions that informed the survey’s development, and nearly 600 women completed the 78-question survey. (Throughout this piece, we use “women” to describe survey respondents in total, though the survey intentionally also included people who identify as nonbinary, gender fluid, and transgender. In instances where there are unique, significant differences in experiences, we make note of them.)

This data story shares what we learned from women of color experiencing homelessness as individuals in Los Angeles. We explore four key themes that emerged from the survey and pair them with women’s descriptions of homelessness and their needs and preferences for housing. We hope that by viewing these data alongside women’s voices and perspectives, policymakers, advocates, and opinion leaders will better understand the unique reality of women of color experiencing homelessness as individuals and work to advance the systemic changes needed to improve their lives.

Nearly 3 in 4 women experiencing homelessness as individuals in Los Angeles County are women of color, and Black women make up a disproportionate share

Among the 72 percent of women experiencing homelessness as individuals in Los Angeles who are women of color, Hispanic and Latina women and Black and African American women make up the majority (39 and 27 percent, respectively). Black and African American women are dramatically overrepresented; the share of women experiencing homelessness as individuals who are Black is three times Black women’s share of the county population (27 versus 7.9 percent).

This inequity is the result of numerous systemic factors converging, including housing discrimination and redlining, high eviction rates among Black women, and racial and gender-based wealth gaps. Women are more likely than men to experience domestic abuse, gender-based violence, and sexism in the labor market that can lead to the loss of their homes. Women of color face racial and ethnic disparities in poverty rates, educational attainment, housing discrimination, access to health care, and incarceration that also increase their likelihood of experiencing homelessness.

Racism and sexism and homelessness is a big issue. You’re in a category that no one wants, you’re treated without any humanity.

Women of color are typically unsheltered and have multiple, long episodes of homelessness

Women of color in Los Angeles often endured homelessness for longer than they expected, with current episodes of homelessness ranging from two and a half to three and a half years. On average, these episodes spanned 1,285.5 days (about 3 years and 6 months) for Hispanic and Latina women, 1,079.5 days (about 3 years) for Black and African American women, and 959.9 days (about 2 years and 7 months) for Indigenous and Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) women. (The latter group includes women who are Asian and Asian American; American Indian, Alaska Native, and Indigenous; and Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander. We combined these groups for our analysis because their individual sample sizes were too small to otherwise have analytical power; we recognize the limitations of combining groups and, in general, aim to use the most-specific groups when possible.)

More than half of all women experiencing homelessness as individuals had been homeless at least once before (57.3 percent). Among women of color, 25.8 percent of multiracial women, 25 percent of AAPI and Indigenous women, 21.3 percent of Hispanic and Latina women, and 17.5 percent of Black and African American women had entered homelessness two or more times in the past three years.

The duration and number of women’s homelessness episodes take on new meaning considering that about 70 percent of women experiencing homelessness as individuals most often slept in unsheltered locations, including on the streets (40.2 percent); in cars, vans, or RVs (23.2 percent); on beaches or riverbeds (3.5 percent); and on public transportation (2.1 percent).

What I have done and what other women I know have done, in order to stay safe on these streets, [is] you have to sleep at a park where kids play with parents and stay up all night.

Lack of shelter places women’s physical and mental health at risk and makes it harder for them to access basic needs, such as hygiene supplies and facilities. For example, unsheltered women in Los Angeles were significantly more likely than sheltered women to find it difficult or very difficult to access a restroom (77.7 versus 47.2 percent).

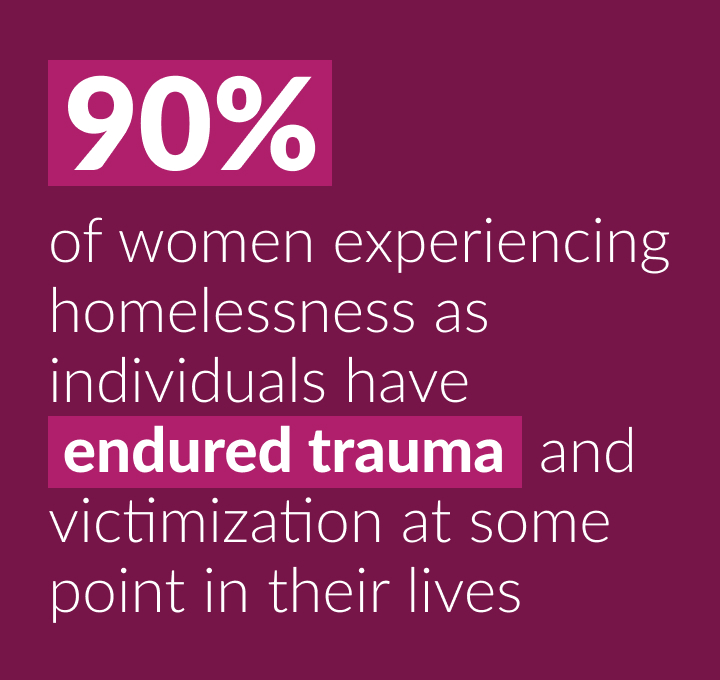

Women of color experience high rates of trauma and victimization

More than 90 percent of women experiencing homelessness alone in Los Angeles County have endured trauma and victimization at some point in their lives. That most frequently meant having had something stolen (73.8 percent); being repeatedly harassed or threatened (57.1 percent); and being threatened, physically hit, or made to feel unsafe by a romantic partner (48.4 percent).

Victimization rates varied among women of color. More than 60 percent had had something stolen from them (about 75 percent of Hispanic and Latina women, 70 percent of Black and African American women, and 60.5 percent of AAPI and Indigenous women). More than half had been repeatedly harassed or threatened (58 percent of Hispanic and Latina women, 56 percent of AAPI and Indigenous women, and 55 percent of Black and African American women). In addition, at least 40 percent of women of color had been threatened, physically hit, or made to feel unsafe by a romantic partner (58 percent of AAPI and Indigenous women, 56 percent of Hispanic and Latina women, and 40 percent of Black and African American women).

I became homeless because of the fear. You expect your husband to be loving and caring, and who would expect that he will kill you. And when he broke my arm, the police gave me a brochure, but I was scared to leave.

These experiences were particularly severe for women who identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer, or another sexual orientation other than straight (LGBQ+). LGBQ+ women of any race (53.6 percent) were significantly more likely to have been threatened or verbally or physically attacked because of their sexual orientation than straight women who are Hispanic and Latina (19.9 percent), Black and African American (13.8 percent), or white (10.7 percent). (Because of small sample sizes for AAPI and Indigenous and multiracial women, we exclude their rates here.)

Women who are part of marginalized groups, including women of color and LGBQ+ women, may also face trauma from interactions with public systems. More than one-third of AAPI and Indigenous women (43.1 percent), Hispanic and Latina women (36.2 percent), and Black and African American women (35.6 percent) experiencing homelessness as individuals were involved with child protective services and foster care as children. More than 50 percent of LGBQ+ women were involved with these systems as children.

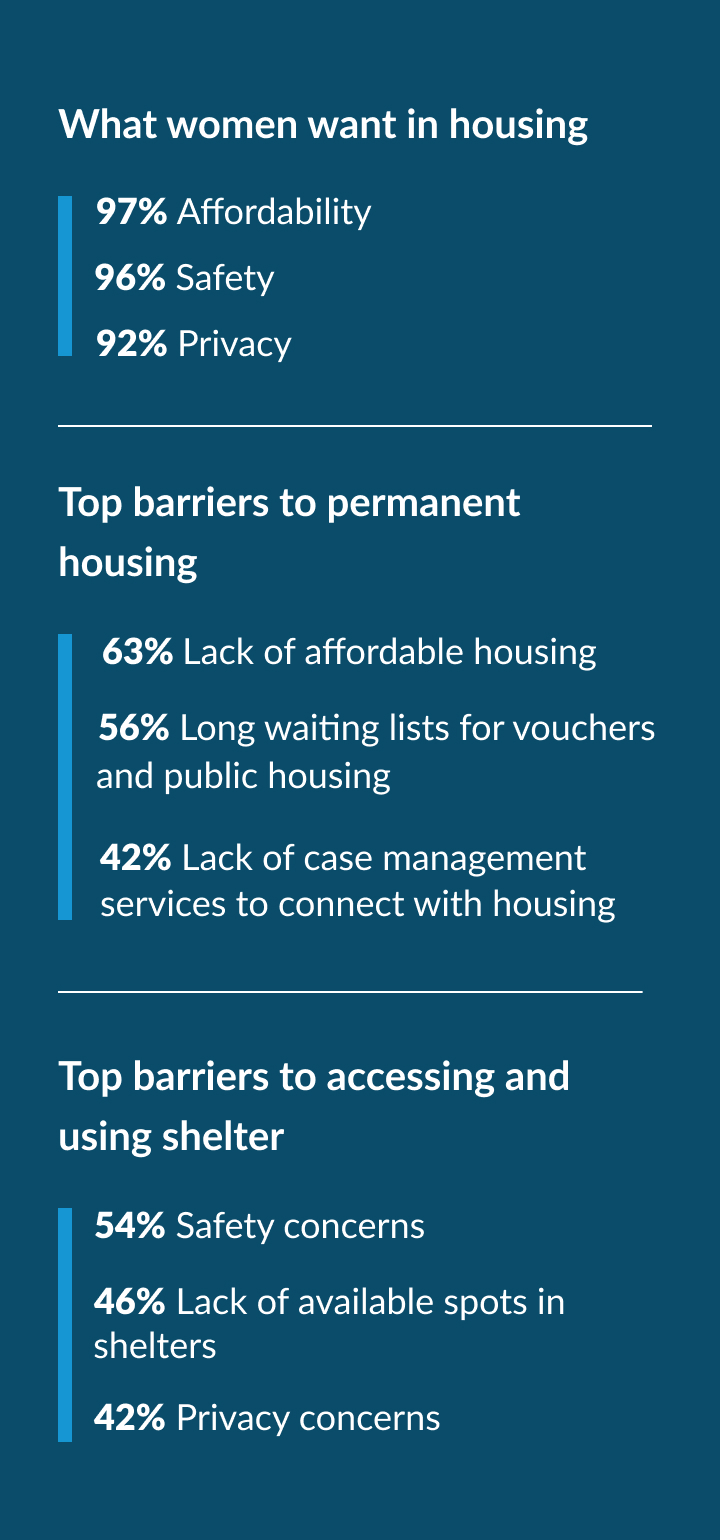

All women want safety, affordability, and privacy in housing and shelter, but women of color face unique barriers

Each woman experiencing homelessness as an individual in Los Angeles has a unique story, but the women we surveyed and spoke with had something in common: they all wanted their housing to be safe, affordable, and private. However, the experiences they described made clear that the shelter and housing options available to them rarely meet these needs.

Apart from the safety, which is important, [I want] a place that is going to be like a refuge to rest and not worry that a person is going to harass me, bully me, be misunderstood. A place where you can have people visit you and accept you.

Among all women, the most common barrier to accessing and using shelter was safety concerns (53.6 percent). However, these barriers varied by women’s races and ethnicities. For instance, more than two-thirds of multiracial women reported concerns about how shelter staff would treat them as a barrier to using shelter (67.9 percent). This far outpaces the rates at which other racial and ethnic groups reported this concern, all of which are still troublingly high: 40 percent for Black and African American women, 31.3 percent for Hispanic and Latina women, and 25.8 percent for white women.

Accessing housing presented different challenges. More than half of women reported a lack of affordable housing and long waiting lists for vouchers or public housing as reasons they couldn’t obtain either temporary or permanent housing (63.1 and 55.9 percent).

Barriers to housing also differed by women’s racial and ethnic identities and by their sheltered status. Among unsheltered women—who make up 75 percent of all women facing homelessness as individuals in Los Angeles—those who are Hispanic and Latina were significantly more likely than their white counterparts to report not having been assessed by coordinated entry as an obstacle to accessing permanent housing (28.9 versus 9.8 percent).

Among sheltered women, those who are multiracial were significantly more likely than white women to cite a lack of public transportation near housing options as a barrier to housing (39.4 versus 20.6 percent). Multiracial sheltered women were also more likely than their white counterparts to report that they were still waiting for a housing placement after coordinated entry (51.0 versus 31.0 percent). In addition, sheltered Black and African American women were significantly more likely than sheltered white women to report criminal legal system involvement as limiting their access to permanent housing (11.7 versus 5.8 percent).

Ending homelessness among women is possible

Survey data and insights from women make one thing clear: we are failing women of color experiencing homelessness as individuals in Los Angeles. Changes to policy and practice could solve this and help more women—in Los Angeles and elsewhere—exit homelessness. Policymakers at the local, state, and federal levels, service providers, and advocates have the power to fund and implement those solutions. They each have a role to play in advancing four urgently needed programmatic and policy changes that could radically improve women’s lives:

- Provide housing assistance to everyone who qualifies. Women cited a lack of affordable housing, long waiting lists for housing assistance, and limited access to housing services as their biggest barriers to permanent housing. Universal housing vouchers, which would essentially increase funding for housing assistance to match the level of need, would reduce obstacles to housing not just for individual women but for all people experiencing or at risk of homelessness. However, Congress would need to increase funding for vouchers so that all who are eligible can access them.

- Ensure women’s safety in unsheltered and sheltered locations. With women facing substantial trauma and victimization and many reporting avoiding shelters because of safety concerns, it’s unsurprising that women named safety as their top priority in housing. Several changes could offer better protection to women in both sheltered and unsheltered locations. In sheltered situations, women suggested establishing women-only spaces, noncongregate interim housing and shelter for individuals, and a security presence that makes women feel safe. In unsheltered situations, women said access to safe parking while waiting for housing and help paying for the costs of a vehicle could help them feel and stay safe. It’s also essential that all programs and services offer supports for survivors of domestic violence, given women’s high victimization rates.

- Enhance dignity in the absence of housing. The women we surveyed and spoke with wanted to have their humanity acknowledged and to feel connected and cared for, but their experiences seeking shelter, hygiene facilities and supplies, and public programs and services were often the opposite. Providing women with safe, reliable places to address their most basic needs and store their personal belongings would recognize their humanity in a way that’s currently lacking. Ensuring service providers across the homelessness response system are empathetic and minimizing the burden of accessing services, such as by requiring fewer invasive assessments and physical searches of women and their belongings, are also essential.

- Hold systems and programs accountable for ensuring equitable outcomes for marginalized groups. None of the preceding recommendations can be achieved without addressing the disparities faced by women experiencing homelessness as individuals with marginalized identities, such as women of color, those who are transgender or nonbinary, and women with disabilities. The opportunities for doing so are numerous: policymakers and housing service providers should work together to ensure women have choices in housing and that those choices recognize and enhance their autonomy. They should also advance policies and programs that would support women’s access to high-quality, culturally responsive physical and mental health care. In addition, service providers should be trained to provide resources and care in a gender-affirming, compassionate way and to better recognize and respond to how women’s needs differ by their age and developmental stage.

These recommendations hold promise for transforming the lives of women of color experiencing homelessness as individuals because they are directly informed by their needs and experiences. By centering those facing some of the greatest barriers to accessing permanent housing, they also have the potential to improve outcomes for all people enduring homelessness in the US.

ABOUT

The information presented is based on listening sessions and the Los Angeles County Women’s Needs Assessment survey, both of which were conducted in 2022. Ninety-two women experiencing homelessness and women who had been housed recently (since 2020) across all eight Service Planning Areas in Los Angeles County participated in listening sessions, which informed the survey design. Five hundred eighty-six women completed the 78-question survey. These women met the following eligibility criteria: they identified as a woman and/or as nonbinary or transgender, were at least 18 years old at the time of the survey, were experiencing homelessness at the time of the survey, were seeking services as an individual at the time of the survey, and had not participated in the survey previously during the data collection period.

Our data have several limitations. Throughout this piece, we use “women” to describe survey respondents in total, though the survey intentionally also included people who identify as nonbinary, gender fluid, and transgender and who may not identify as women. Nearly 95 percent of respondents identified as women, and 3.7 percent identified as a gender other than exclusively a woman or a man. In a separate question, 7.7 percent of people identified as transgender. Additionally, the survey and listening sessions only captured information from English- and Spanish-speaking women. We also could not analyze some racial and ethnic subgroups that are overrepresented among people experiencing homelessness, specifically Indigenous people, because of low response rates. For this reason, we combine Asian and Asian American; American Indian, Alaska Native, and Indigenous; and Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander women into one group. In addition, though our analysis includes comparisons of LGBQ+ women’s and straight women’s experiences, small sample sizes prevent us from doing additional analyses with specific sexual orientations (e.g., comparing differences between lesbian, gay, bisexual, and/or queer women). Similarly, we could not include a subgroup analysis comparing cisgender women’s experiences with those of transgender women and nonbinary individuals.

See our accompanying report for more information.

PROJECT CREDITS

This data story was funded by the Hilton Foundation as part of Urban’s Housing Justice Initiative. It builds on research funded by the County of Los Angeles Homeless Initiative and the Downtown Women’s Center. The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Urban Institute, its trustees, or its funders. Funders do not determine research findings or the insights and recommendations of our experts. More information on our funding principles is available here. Read our terms of service here.

We thank our partner Sofia Herrera of the Hub for Urban Initiatives who served as the co–principal investigator for the 2022 Los Angeles County Women’s Needs Assessment. The work completed as part of the original scope of the needs assessment served as the basis for this secondary analysis. We also thank members of the Women’s Needs Assessment Steering Committee, the Housing Justice Community Advisory Board, and staff members of the Downtown Women’s Center for their review and contributions to this feature.

RESEARCH Samantha Batko, Lynden Bond, and Kaela Girod

DESIGN Christina Baird

DEVELOPMENT Rachel Marconi

EDITING Irene Koo

WRITING Rachel Kenney

Tune in and subscribe today.

The Urban Institute podcast, Evidence in Action, inspires changemakers to lead with evidence and act with equity. Cohosted by Urban President Sarah Rosen Wartell and Executive Vice President Kimberlyn Leary, every episode features in-depth discussions with experts and leaders on topics ranging from how to advance equity, to designing innovative solutions that achieve community impact, to what it means to practice evidence-based leadership.